In the spring of 2008, Barack Obama announced his bid to become the next Ronald Reagan. During an interview with the Reno Gazette-Journal, the Democratic candidate predicted that his election would change America’s economic policy paradigm as thoroughly as the Gipper’s victory had three decades earlier.

“I think part of what’s different are the times,” Obama said. “I do think that, for example, the 1980 election was different. I think Ronald Reagan changed the trajectory of America in a way that, you know, Richard Nixon did not and in a way that Bill Clinton did not. He put us on a fundamentally different path because the country was ready for it.”

“I think we are in one of those times right now,” the candidate continued, “where people feel like things as they are going, aren’t working, that we’re bogged down in the same arguments that we’ve been having and they’re not useful. And the Republican approach I think has played itself out … You look at the economic policies that are being debated among the presidential candidates, it’s all tax cuts. Well, we’ve done that. We’ve tried it … so some of it’s the times.”

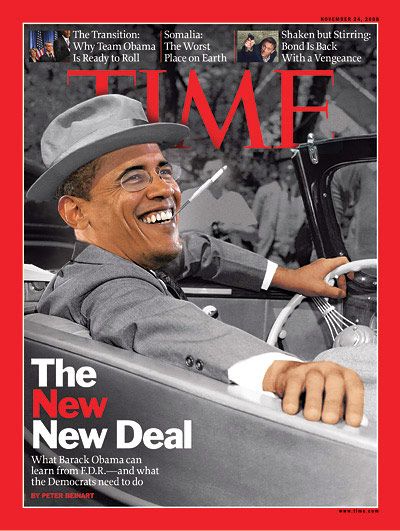

It took eight months for Obama’s words to attain the aura of prophecy. By the day of his inauguration, Reagan-era orthodoxies had apparently driven the global financial system and conservative movement to the brink of collapse. Even America’s high priests of supply-side gospel had fallen into crises of faith. Alan Greenspan told Congress that the crash had exposed a “flaw” in his worldview so profound, its exposure had left him in a “state of shocked disbelief.” Within weeks, Greenspan and Republican senator Lindsey Graham were imploring the White House to consider a temporary nationalization of the American banking system. The political press was replete with variations on Obama’s months-old remarks: A “New Liberal Order” was arising from the ashes of the Bush presidency — the emerging Democratic majority had finally arrived. On the cover of Time magazine, Obama’s Photoshopped face smiled through FDR’s signature accessories as a headline heralded the coming of a “New New Deal.”

And then, the times changed. Once the Obama administration got the big banks off life support and Mitch McConnell’s minority got its bearings, the dream of a rapid realignment quickly died. Conservatives had little trouble recasting 2008’s apparent humiliation of market fundamentalism as an indictment of big government largesse: Lawless banks hadn’t crashed the global economy by defrauding their customers; bleeding-heart liberals had done so by forcing banks to subsidize the parasitism of the spendthrift poor. Thus, far from inducing a leftward lurch in Republican economic thinking, Obama’s election coincided with a reactionary resurgence. By 2011, Republicans weren’t seeking accomodation with the president’s ascendent creed; he was seeking accomodation with theirs. Two years into the “New New Deal,” with unemployment still near double digits, the Democratic president was struggling to persuade Republicans to help him cut Social Security. Six years after that, Donald Trump presided over yet another round of supply-side tax cuts.

Even as the political basis for a leftward realignment on economic policy crumbled, the empirical basis for such a development only grew stronger. Conservatives predicted that Obama’s stimulus spending would trigger runaway inflation; instead, consumer prices remained stubbornly low. The center-right insisted that fiscal austerity could supercharge growth; Europe implemented its prescription and plunged itself into a deeper hole. Meanwhile, as the recovery delivered soaring asset prices to owners of capital, but only tepid wage gains to ordinary workers, America’s inequality problem became too conspicuous for even conservative-minded economists to ignore. And all the while, the steadily deepening climate crisis was transforming the notion that America needed a new green industrial policy from an article of far-left faith into a pillar of scientific consensus.

Now, 12 years after the financial crisis, and three years into Donald Trump’s post-truth presidency, there are mounting signs that these empirical realities are finally making a dent in political ones — that Obama’s prophesied realignment may be making its belated arrival.

Some Republicans are getting in touch with their inner Eisenhower.

In the summer of 2012, Mitt Romney told African-Americans that if they wanted “free stuff” from the government, they should “vote for someone else.” Months later, the GOP nominee derided 47 percent of the U.S. public as incurable layabouts, whose sense of “personal responsibility and care for their lives” had eroded so completely, the Republican Party no longer had anything to offer them.

Seven years later, Romney signed onto a bill that would hike inheritance taxes on millionaires and billionaires, and use the revenue to provide unconditional cash assistance to all low-income parents, regardless of their employment status. The Romney-Bennet refundable child tax credit would be the first in American history to provide financial relief to the very poorest families in the U.S. In lending his name to the policy, Romney adopted a position on child welfare to the left of many congressional Democrats.

Romney’s change of heart on the propriety of cajoling indigent parents into the labor force by condemning their children to poverty is idiosyncratic in Washington; no other Republican has signed onto his bill. But it is nevertheless indicative of a broader, leftward current in GOP economic policy thinking.

Earlier this month, GOP state legislators in Kansas agreed to expand its Medicaid program without work requirements, as long as the state also increased subsidies for those purchasing private insurance. Meanwhile, in D.C., House Republicans began work on a conservative alternative to the Green New Deal. According to Axios, the emerging legislation would double “federal investment in basic research and fundamental science”; establish special “lower tax rates for U.S. companies exporting clean energy technology”; expand tax credits for firms that sequester CO2; “redirect foreign aid to help countries that have rivers most polluted with plastic”; and provide unspecified incentives and funding to spur the planting of 1 trillion trees. As a response to the climate crisis, this is comically inept. But as a House Republican policy priority, it is bizarrely constructive. The GOP leadership has tacitly affirmed the need for the U.S. government to increase its investments in scientific research, and pursue a green industrial policy — which is to say, catalyze growth in the clean-energy and carbon-sequestration sectors through targeted interventions in the market economy. The kind of industrial policy they propose is deeply inadequate to the scale of the ecological problem. But the legislation’s ostensible goals —encouraging the rapid development and export of clean-energy technologies in order to reduce the carbon intensity of economic growth in the developing world — are vital ones (and broadly similar to those in Elizabeth Warren’s green industrial policy).

Reactionary billionaires remain the GOP’s biggest stockholders. But they no longer have a monopoly on the party’s voting shares.

Viewed in isolation, each of these developments could be dismissed as a meaningless gesture. After all, stray messaging bills aside, the Trump-era GOP’s economic policies have been historically reactionary. The party very nearly threw millions of Americans off of public health insurance, slashed taxes on the wealthy, and left corporate foxes guarding each of the regulatory state’s hen houses. On low-visibility matters of executive branch policy, the Trump administration has been almost comically regressive, fighting to expand the liberty of coal companies to dump mining waste in streams, let financial advisers gamble with retirees’ money, and free employers from the burden of logging workplace injuries, among many other things. Meanwhile, on the similarly low-salience subject of federal judicial appointments, Trump has been stacking the courts with plutocracy superfans.

The GOP is not becoming any less interested in taking from the poor (or working class, or environment, or future generations) to give to its top shareholders. The party’s influence peddling remains unconstrained by egalitarian inhibitions. But its economic policy-making is becoming a bit less constrained by Ayn Randian scruples. Romney is alone in supporting refundable child tax credits for the nonworking poor. But a broader swath of the GOP is warming to small-bore, family-based social welfare policies, including refundable child tax credits for working parents and modest forms of paid family leave. Kevin McCarthy’s climate bill may be a mere stunt, but the House Minority Leader is not alone in signaling a heretical interest in (nonmilitary) industrial policy; Republican senators Josh Hawley and Marco Rubio have made similar noises in recent months, with the Florida senator issuing a report on the harms of neoliberal “financialization” that actually cited the work of socialist economists. In other words, while Republicans remain happy to do the bidding of libertarian billionaires when it suits their political interests, they appear more willing to opportunistically flout the Koch Network’s preferences than they were during the Obama years.

This fact may reflect the changing class composition of the GOP coalition as affluent suburbs defect to blue America, or the increasingly conspicuous tension between cultural conservatism and market fundamentalism, or the trauma of the failed Obamacare repeal effort and ensuing midterm blood bath. Or it may simply reflect the fact that a Republican is currently in the Oval Office; the right has always looked more kindly on deficit spending and social welfare provisions when its people are at the wheel.

The times, they are, uh, changing?

But even if the GOP’s flirtations with a post-Reaganite economic paradigm prove limited and conditional, they could nevertheless be of real consequence. For one thing, Romney and Rubio’s leftward drift helps fortify the Democratic Party’s more robust one. What passes for “centrism” in the 2020 Democratic primary would have been coded as progressivism in 2016, 2008, or any other cycle in my lifetime. Today, Joe Biden’s climate plan is more comprehensive than Bernie Sanders’s was four years, according to the left-wing think tank Data for Progress. Michael Bennet — whose anemic campaign is sustained by its sheer incredulity at the left’s imprudence — is nevertheless running on a $6 trillion expansion of the social safety net financed by progressive tax increases.

Given the biases of the Senate, the significance of the Democratic field’s leftward lurch largely hinges on whether the party’s most conservative senators start bending in the same direction. And when Mitt Romney makes unconditional assistance to poor families a bipartisan concept, or House Republicans tacitly affirm the need for Uncle Sam to “pick winners and losers” in the energy market, it becomes a bit easier for Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema to swim with the progressive tide.

Similarly, if even two or three Republican senators retain their heterodox hobbyhorses when a Democratic president takes power, our government will regain the capacity to meaningfully legislate in times of divided rule. The fundamental obstacle to federal progress on climate or poverty or health-care reform over the past decade has not been the GOP’s stubborn insistence on inadequate solutions, but rather, its fanatical commitment to making our problems worse. There can be no bipartisan compromise on climate if the Republican position is that the government should do everything in its power to maximize carbon emissions — from subsidizing failing coal plants to rolling back fuel-efficiency standards in defiance of the auto industry’s preferences. And there can be no consensus approach to reducing poverty if the GOP’s prescription is to coerce the unemployed into the labor force by denying their families’ access to health care and housing. By contrast, if the partisan divide on climate and poverty is merely over exactly how much to subsidize green technology, increase foreign aid to climate-vulnerable countries, ramp up federal spending on basic research, and expand cash support to the neediest, then it should be possible for Congress to mount a productive legislative response to America’s most pressing challenges.

To be sure, the ifs in that last paragraph are big. Although the parties may be growing marginally less polarized on some economic issues, the cultural antagonism between red and blue America has rarely been fiercer. The notion that the Democratic Party — and thus, any elections it wins — are fundamentally illegitimate appears more widespread in conservative circles than ever before. Just because Marco Rubio’s staffers have read some iconoclastic economists doesn’t mean that the GOP’s “fever” is about to break.

Yet when one puts the GOP’s recent post-Reaganite gestures next to the left turn in mainstream economic thought, the Davos set’s growing interest in shoring up the legitimacy of the order they sit atop with palliative policies on climate and inequality, the British Tories’ recent triangulation on economics in response to its own influx of non-college-educated voters, and the resurgent hegemony of tax-and-spend liberalism within the Democratic Party’s tent, it’s hard not to entertain the possibility that these times are different — and that the 2020 election just might put America on a “fundamentally different path.”